Article written by Seth Larsen

If you're a strength athlete, by now you have developed a serious relationship with upper body pressing movements. For some, it is loving partnership full of constant gains and minimal pain. For others, it is a nasty struggle of a relationship, characterized by nagging injuries and difficulty making progress. For most of us, however, it is like many of our other relationships in life; we go through the ups and downs, but can't give it up due to its importance. As for myself, I have a bit of a love-hate relationship with pressing. Some of my presses are fun, painless, and productive, while others are humbling and frustrating. At the end of the day, we all need to press for a multitude of reasons.

Some people are naturally good pressers. This is often due to variations in anatomy such as arm length and shoulder mobility, but can also be attributed to certain muscle groups that are just stronger than others. For those that pressing does not come to easily, the reasons are no different. The optimal combination of beneficial lever length, shoulder and thoracic mobility, and strength of specific muscles is what makes a strong presser. Having just one or two of these things is not quite enough. This is why female athletes tend to have weaker presses in comparison to their lower body movements than male athletes do. While the mobility of women is often far better than their male counterparts, the genetic differences in upper body strength is difficult to overcome. I'm not going to beat the dead horse of mobility for once, so I'd like to focus on the different muscle groups used in each type of pressing we see in our respective strength sports.

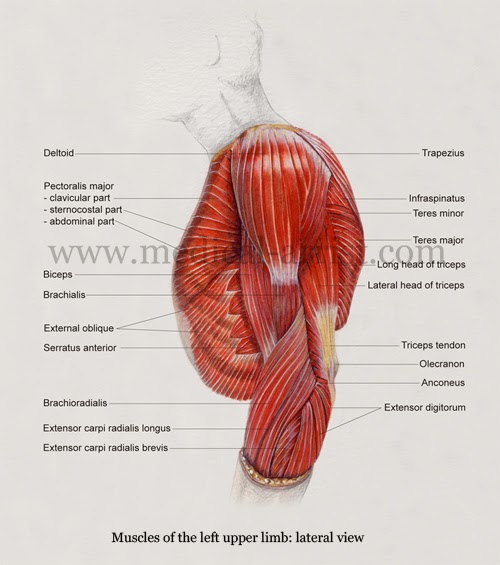

If you've read any of my previous articles, you know that we can't go into the movements before we discuss the anatomy. Real depth into all the individual muscles isn't necessary here, but it's important for us to have a basic understanding of them in relation to the different presses. Let's start with the deltoids. This muscle has three heads: the clavicular, the acromial, and the spinal. Colloquially, these are known as the front, middle, and rear deltoids. While the primary functions of the three heads together are abduction (moving the arm away from the body) and flexion (raising the arm over the head), the individual heads also have specific functions. For example, the clavicular head (front delt) is most active in abduction when the arm is externally rotated (palms facing forward), is a major shoulder flexor, and also assists the pec major in shoulder flexion when the elbow is below the shoulder. The acromial head (middle delt) is most active in abduction when the arm is internally rotated (palms facing backwards) and also acts in shoulder flexion when the arm is externally rotated. The spinal head (rear delt) is the major shoulder extensor/hyperextensor, assists the latissimus dorsi and other muscles in rowing type movements, and is a strong external rotator of the arm. Together with assistance by the four small muscles of the rotator cuff, the three heads of the deltoid are extremely important not just in overhead pressing, but in all upper body movements.

Now for the pectoralis major and minor. The pectoralis major is the big gun here, with primary functions of shoulder flexion, arm adduction (moving the arm towards the body's midline), and internal rotation of the shoulder. This last function is why those of us with imbalanced pectoral muscle development compared to the muscles on the posterior of the upper body walk around with their shoulders rolled forward. No less important, the pec major keeps the arms attached to the body at the shoulder. Because of this, lack of strength in the pectoral muscles can be a recipe for disaster when trying to prevent shoulder injuries such as dislocations and separations. The pectoralis minor lies underneath the pec major, and is designed for stability. It pulls the scapula downwards and towards the body's midline, and due to this function is sometimes described as the “fifth rotator cuff muscle.” However, if it is too tight or overdeveloped, it can worsen the gorilla-like appearance described above.

The musculature of the upper back, such as the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and rhomboids is not often thought of as important for pressing, as these muscles are not prime movers in the bench or overhead press. However, they are of paramount importance when it comes to stability. Their individual actions vary, but for our purposes we can think of them as the foundation on which heavy pressing can be built. A strong upper back provides a shelf of sorts for the pressing movements, and keeps the scapulae and thoracic spine in proper position to execute a solid press. If you can find a strong presser with a small and weak upper back, let me know, because I have never seen one.

Last and most certainly not least, the triceps. We all know that their primary function is that of elbow extension, which is necessary for any press. The three heads of the triceps are as follows: the long, the medial, and the lateral heads. The long head is widely considered to be the strongest, as it has the most mass, and is most active in sustained generation of extensory force. It also helps to adduct the shoulder in synergy with surrounding muscles. The lateral head contracts more rapidly, and as such can generate high-intensity force quickly. The medial head is smaller, and is used in more precise movements requiring a lower amount of force. The differences between these heads are not crucial to our discussion, so just think of the triceps as your prime elbow extensors that also have the ability to fixate the elbow in different degrees of the flexion/extension cycle.

At last we can move on to the reason I'm sure most of you are reading this article: the different pressing movements. First, the overhead press. As a strongman, I need to be skilled at pressing a number of different implements, and thus use many variations of the overhead press in my training. For you CrossFolk, the variety you see in your WODs and competitions requires proficiency in multiple overhead pressing disciplines as well. Powerlifters, who more often than not use the overhead press as an accessory lift to increase their bench press tend not to utilize the same level of variety in this movement, but changing hand positioning and arm angles can help them to assess and improve on weak points as well. I'll start with the different implements. Because the movements performed with an axle and barbell are roughly the same, I will not differentiate between the two here. The difference in range of motion between the two is negligible as well. However, when compared to a log press, an axle or barbell overhead press requires a significantly longer range of motion.

Due to this increased ROM, the pectoralis major is utilized to a greater degree in the initiation of the movement, as the elbows begin far below the shoulder joint. This is not to say that it compares to a bench press, which I will discuss later, but the pecs are definitely activated when performing this type of press. The longer range of motion also allows for increased time to generate force through the deltoids, meaning the bar should be moving faster when the triceps have to kick in to lock it out and finish the press. Not surprisingly, this takes some of the stress off of the triceps. In addition to the ROM, the hand positioning on a barbell/axle is different from a log. The shoulders are externally rotated, placing more stress on the rear deltoids. The front delts are still the prime movers here, but they have help from the pec major and rear delts. The middle deltoids are also active here, as they flex the shoulder in external rotation, but this is not their primary function.

Although I do not have any specific data or information about anatomical and biomechanical differences to support it, I have also noticed in my own training that it is easier to be explosive with an axle or barbell than a log. Speaking with other athletes, they have agreed with me that especially when performing a push press or jerk, the transfer of force from the legs and hips through the upper body into a bar is easier than with a log. Because of this, I will go on record to say that it is often easier to put greater weights overhead with a barbell or axle.

For myself and many others, the log is brutal piece of equipment. It generally requires more brute strength to press than a bar, and definitely activates different muscles. First, because a properly performed log press starts with the elbows high, the pecs are all but taken out of the equation. Without their assistance, it places a significantly larger amount of stress on the front deltoids. Personally, I have never had a front delt pump like the one I get from high-rep log strict presses. Because the neutral grip is on its way to internal rotation, there is also greater activation in the middle deltoids. This neutral grip also provides greater triceps activation, which, coupled with the somewhat “backwards” pressing motion of the log and the fact that the triceps start working right away due to the log's starting position means that locking out a log overhead requires significantly more triceps strength than does a bar. The backward lean in the starting position also places more stress on the lower back than any other pressing movement. Finally, because of the awkwardness and inconsistent weight distribution on some logs, upper back strength and stability is far more important when pressing it. Have you ever seen Big Z's back? Look anywhere, because no matter where you're reading this from you can probably still see it. There's a reason he was the first man to ever put a 500lb log over his head.

| Make sure the log kisses your beard on each rep |

Dumbbell overhead presses are also a valuable tool in any lifter's toolkit. Depending on which direction your palms are facing, different muscles are activated. The Arnold press, for example, has been touted to hit all three heads of the deltoid equally due to the rotation that occurs during the press. While this isn't entirely accurate, as the front delts do the most work regardless, the Arnold press does provide a more even activation of the three heads of the deltoid than any other individual pressing movement. The best part about dumbbells, however, is their ability to correct imbalances. Although this is a gross oversimplification, it can be argued that they require more rotator cuff activation due to the implements not being fixed and the arms moving independently. Furthermore, as most of us have one dominant arm, rep schemes can be adjusted to strengthen the weaker arm. In addition to reducing the risk of future injury, this means that when you go back to the bar or log, you will have a more even press. A more even press has a much greater likelihood of making it to lockout, so get those imbalances fixed.

Not only should implements be varied in training to activate and strengthen different muscles, different overhead movements should be used as well. The old standby is the strict or military press. I know, I know; it's not a true military press unless your feet are together, but the terms are often used interchangeably, so relax. I'll stick to calling it a strict press so that nobody's jimmies get too rustled. The strict press is essentially all about shoulder (mostly front delts) and triceps strength. There is no dip and drive, no flexion at the hips, and no dropping under to catch it at lockout. This is the staple in many overhead pressing programs, especially for powerlifters. It is by far the best way to develop stronger shoulders. Although I prefer the standing strict press, as it requires more stability and is more similar to what strong(wo)men and CrossFitters do in competition, seated presses have also been used with great success by many athletes. They take the legs out of it completely and often allow you to press more weight for more reps without tiring out the lower body and core musculature. The push press is many athletes' preferred method of overhead pressing maximal weight, but because of the leg and hip drive, it takes some of the stress off of the shoulders and triceps. Strength in these muscles is still necessary for a heavy push press, especially at lockout, but some weaknesses can be covered up with strong legs and proper timing. If you plan on competing at a high level in anything but powerlifting, I suggest developing your technique in the push press. I have seen far too many athletes try to strict press everything in competition and leave a significant amount of weight on the table because of it.

Similar to the push press, push/power jerks (bar is caught in a quarter squat) and split jerks (bar is caught with a split stance), use a lot of leg drive. These are even more technique-intensive, but can be very successful if done properly. Weightlifters have put up ridiculous overhead numbers for decades using these movements. Due to the catch, however, they will take even more out of your legs and back than a push press, and it won't be considered a completed rep in competition until you are standing straight up with the weight over your head. All three of these movements can be performed with the bar racked behind the neck as well. Especially when done with a wide/snatch grip (such as the now popular Klokov press), behind the neck pressing places a significantly greater amount of stress on the rear deltoids and upper back musculature due to the extreme amount of external rotation needed to achieve these positions. They also require better thoracic mechanics and shoulder mobility to do perform correctly. Many of us with tight shoulders may not be able to perform these movements at all. If you have a shoulder injury, be wary of these and make sure you do them properly.

Start out light and get the technique down or you could be paying for it (quite literally, if the injury is severe) for a long time. Even if you have no injury history, be sure to work on your shoulder mechanics and mobility before attempting any behind the neck pressing. In fact, make sure to do that regardless of what type of pressing you are doing. Sorry, I said I wouldn't get on my mobility soapbox. Moving on...

And now for what the powerlifters and gym bros have been waiting for: the bench press! Personally, I hate benching. It's uncomfortable, more dangerous than overhead pressing, and the benches always seem to be taken. But more than that, I'm not very good at it. Due to that painful fact, I'm not going to speak in detail here about specific bench techniques, set-up, or the NEW AND IMPROVED SUPER-SECRET WORKOUT TO PUT 100LB ON YOUR BENCH IN 2 WEEKS! Because that totally exists, brah. I'll stick to the common types of bench pressing and the muscles that they activate, starting with everybody's favorite, the barbell flat bench press. Although it has been said that a powerlifting style bench press is more triceps than pectoralis dominant, I think you'd be hard pressed to find a truly strong bencher with small, weak pecs. We are talking about a raw bench press here, so leave the bench shirts out of the conversation, as they not only look silly, but they completely change the lift. Generally, the main reason one is benching is to develop pectoral strength and hypertrophy, and the barbell flat bench is great for that. The anterior and middle deltoids are also used here, as are the triceps, but the degree to which they are activated is dependent both on your bar path and grip width, respectively. The differences in deltoid activation in relation to the path of the bar would be better explained by an accomplished powerlifter, and as I am still new to that sport, I'm not going to going to delve into it. Besides, if you are using the flat bench press to train your shoulders, you've got bigger problems than your bar path. The triceps are most affected by the width of your grip on the bar.

A wider grip is going to place more stress on the pecs, while a narrower grip is going to place more stress on the triceps. This is why many strongmen still perform a significant amount of close-grip bench presses, even though the bench is not a competition lift in that sport. These grip variations can be used in incline and decline bench presses as well for the same purpose.

Speaking of changing the bench angle, let's talk about incline and decline presses. Despite the fact that bodybuilders like to say that they build your “upper chest” and “lower chest,” respectively, this isn't actually true. There is no “upper chest” muscle. What about pectoralis lowerus? Never heard of it. Although it is true that incline presses place slightly more stress on the clavicular head of your pectoralis major than flat bench presses, the entirety of the pectoralis major still fires during an incline press. What an incline bench press really does is allow you to overload your deltoids with more weight than you would be able to overhead press while simultaneously training your pecs, albeit to a smaller amount than you would with a flat bench press. This increase in shoulder size strength makes one a stronger bench presser, allowing greater weights to be moved for more reps, ultimately increasing the size of the pecs. Unfortunately, most of those bodybuilders you see with the extremely well developed “upper pecs” have them because of genetics. The variations in insertion points for the pectoralis major are what truly give that shape. Sorry. As far as decline presses, they shorten the range of motion and take stress off of the deltoids, placing an overload on the pecs. This is what makes the chest appear more developed, not some mysterious “lower pec” muscles.

Dumbbells can be used in bench pressing for the same reason as overhead pressing. They can help fix imbalances between the arms, create greater stability, and provide variations in muscle activation by changing the direction the palm is facing, just like with the overhead. Another benefit to using dumbbells on the bench is something I have seen in my own training, while recovering from one of multiple shoulder injuries. With dumbbells, the lifter is not as locked into the bench as he or she would be under a heavy bar. The scapulae have more freedom of movement, so a more comfortable position for the shoulders can be achieved without compromising the lift. There have also been electromyography studies that indicated increased muscle activation in the pectoralis major and minor when performing dumbbell bench presses vs barbell bench presses. If hypertrophy is your main goal, this is definitely something to think about.

It should be pretty clear now that there are a lot of ways to skin a cat when it comes to pressing. Find what presses work for your goals, your body, and most importantly, your injury history. If you have a weak point, use the press that activates the muscles needed to push through it. If your muscular development is lacking in another area, pick a different press. If a certain type of pressing hurts, unless it is a competition lift that is absolutely crucial to your sport of choice, scrap it! There are other ways to get it done. Now get out there and press something!

Seth Larsen has a Bachelor's of Science in Biology and Neuroscience and is a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine candidate for 2015 at Midwestern University. He is a former NASM-CPT and student athletic trainer. He currently serves as a reserve officer in the US Navy Medical Corps while he finishes medical school with a specialization in primary care sports medicine. Seth is a former NCAA football player who now competes as a MW (105kg) strongman, Highland Games athlete, and raw powerlifter.